Synopsis: The Doctor and Peri meet the revolutionary engineer George Stephenson, still some years before he achieved fame. Stephenson has organised a meeting of some of the greatest minds of the age, but the event is threatened by a series of attacks from Luddites intent on wrecking any chance of progress. In reality, the attackers are victims of the Rani, an amoral Time Lord. Wanting to be left alone to her experiments, the Rani is instead coerced into joining forces with the Master against the Doctor…

Chapter Titles

- Prologue

- 1. House Of Evil

- 2. The Scarecrow

- 3. The Old Crone

- 4. Death Fall

- 5. Enter The Rani

- 6. Miasimia Goria

- 7. A Deadly Signature

- 8. Face To Face

- 9. Triumph Of The Master

- 10. A Change Of Loyalty

- 11. Fools Rush In

- 12. An Unpleasant Surprise

- 13. Taken For A Ride

- 14. The Bait

- 15. Metamorphosis

- 16. Life In The Balance

- 17. More Macabre Memorials

- 18. Cave-In

- 19. Birth Of A Carnivore

- 20. The Final Question

- Epilogue

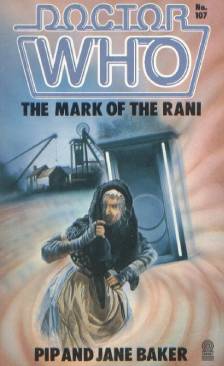

Background: Pip and Jane Baker adapt their own scripts from 1985. Jane Baker becomes only the second woman to have her name on the front of a Target novel. Due to Vengeance on Varos being delayed, the book numbering skips from 105 to 107; it’ll be a couple of years before 106 makes an appearance.

Notes: A prologue full of foreboding and an added TARDIS scene where the Doctor is said to possess an ‘unruly mop of fair curls’ and considers visiting Napoleon while Peri tries to avoid a debate with her travelling companion about English grammar. It’s honestly much funnier than that might sound. It’s Peri who speculates the Daleks might be behind the TARDIS veering off course, despite not having met them at this point (it’s the Doctor on TV). Peri has apparently proven in the past that she’s an expert ‘marksman’. In the Epilogue, we learn that the Doctor finally manages to take Peri to Kew Gardens, but the botany student is distracted, after her experience in Redfern Dell, every flower she looks at appears to have a human face…

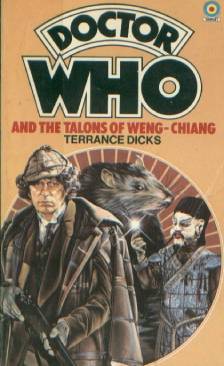

Cover: Andrew Skilleter gives us the Rani disguised as an unidentifiable old crone, accompanied by the Rani’s TARDIS flying through the vortex and in the distance a coal mine. Apparently the unused cover, which used a likeness of Kate O’Mara, was also the one Skilleter was paid the most for. This is the last book to feature his original artwork, although his covers for the VHS releases were also on a selection of Target reprints.

Final Analysis: What a way to start a book: ‘Evil cannot be tasted, seen, or touched.’ Glorious hyperbole from the traditionally understated (!) Pip and Jane as they make the bold claim that the small mining community is so saturated in evil that ‘[if] allowed to flourish, the poisonous epidemic could reduce humankind to a harrowing role that would give a dung beetle superior status.’ Right from the off, P&J’s depiction of the Sixth Doctor is the most likeable and charming we’ve seen so far; his relationship with Peri is teasing but affectionate – he wants to make sure they reach Kew Gardens because it’s somewhere Peri really wants to visit. Knowing the writers’ propensity for sesquipedalian language, we might expect an exuberance for prose of a purple hue. Joking aside, this is refreshingly elegant, neither as florid as some of its recent predecessors nor as basic as a traditional Terrance Dicks. We also know that the Bakers, like Malcolm Hulke, were left-wing and they take great pains to disillusion the reader from imagining this historical trip as a jolly fantasy. Facing the prospect of being abandoned by the Doctor, Peri takes a morose turn:

Sooty eight year old urchins, scavenging for coal, tottered past with heavy baskets. Why weren’t they at school, she wondered, then remembered George Stephenson saying he was working down the mine at the age of nine. How romantic the prospect of this visit had been only a short while ago! Now she thought of the mean streets, cramped dwellings and the lack of hygiene. Hygiene? What if she were ill? Medical science didn’t exist. Depression making her morbid, she gazed at her leg. Suppose she had an accident and it had to be amputated? Anaesthetics hadn’t even been dreamt of! She’d just have to – what was the phrase? – bite on the bullet…