Synopsis: The white heat of British technology is evident in the unveiling of an impressive new tower in the heart of London. At the top sits a powerful super-computer – WOTAN – enabling rapid communication across the world. The computer’s inventor, Professor Brett, is in fact a servant of WOTAN, helping the machine to build a fleet of mobile battle-tanks. Soon, the War Machines appear on the streets of London – and the Doctor is required…

Chapter Titles

- 1 The Home-Coming

- 2 The Super-Computer

- 3 A Night Out

- 4 Servant turned Master

- 5 Putting the Team Together

- 6 Working for the Cause

- 7 A Demonstration of Power

- 8 The One Who Got Away

- 9 Attack and Defence

- 10 Taking to the Streets

- 11 Setting the Trap

- 12 The Showdown

- 13 We Can’t Stay Long

Background: Ian Stuart Black adapts his own scripts for the 1966 story, 22 years and seven months after it aired. On transmission, Kit Pedler was credited as having been responsible for the idea of the story, though it’s still not clear how much of this was just a PR exercise from the production team to highlight their science-based aspirations; if the idea was no more than ‘a computer at the top of the new Post Office Tower’, this wouldn’t be sufficient to lay a claim to a share of the copyright, which might also explain the lack of a credit for Pedler at the front of this book.

Notes: The opening chapter sees Dodo helping the Doctor to steer the TARDIS to its next destination (a task she’s inherited from the recently departed Steven). The Doctor can apparently ‘predict exactly where they would materialise’ [we can look to the start of The Savages for why this might now be the case, as he’s had time to calculate their exact position in the universe for possibly the first time in a while]. Seeing the name ‘Carnaby Street’ on the TARDIS monitor, Dodo reacts as if the street is brand new; it first appeared on documentation in the 1680s and it had been a destination for jazz fans since 1934, slowly transforming into a string of boutiques by about the time Dodo absconded aboard the TARDIS (as a schoolgirl, she was probably a little young for it to have appeared on her radar).

It’s the Doctor, not Dodo, who realises that the new construction in the centre of London is ‘finished’ and he observes that it’s called the ‘Post Office Tower’, though ‘in all probability they would change that name’; opened to the public in May 1966, just two months before the broadcast of the first episode of The War Machines on TV, the building became the ‘British Telecom Tower’ in the mid-1980s before settling on ‘The BT Tower’ in the 90s. William Hartnell’s fluff of the word ‘sense’ to ‘scent’ becomes the Doctor’s intention all along, prompting Dodo to make a joke about London fog. Curiously, Dodo doesn’t know what a milk bar is (they existed in her time and a girl from London would know, but she’s acting as an agent for the reader here). The Doctor is said to be wearing a ‘velvet jacket’.

The duo head to a nearby cafe, where the Doctor speculates that his former companion Ian Chesterton will have become something of note in the world of science and in all probability had something to do with training the staff at the new Tower – and it turns out he’s entirely correct! The Doctor fakes documents that provide him with an introduction, a minor act of subterfuge that then enables him and Dodo to investigate the operations at the top of the Tower – and his credentials are checked and verified by Major Green. Professor Brett has heard Ian Chesterton speak of the Doctor often.

Polly is ‘an attractive girl with long blonde hair and blue eyes’ and she wears a very short skirt that shows off ‘her long and shapely legs’. Dodo thinks that she and Polly might be ‘about the same age – not that Dodo was too sure what her own age was nowadays’ (Dodo was a schoolgirl of about 15 when she first entered the TARDIS and Polly is at least 18 – she’ll have had to attend secretarial school – so that’s a sizeable age gap of Dodo’s for Big Finish to cover there). Polly offers to take Dodo to a new club, The Inferno, which is in Long Acre (that’s a swift 20-minute walk there – and 20 minutes back – so she apparently wangles an early finish on the Friday before the project’s big launch (miraculous in itself!). WOTAN says that ‘The Doctor is required’, not ‘Doctor Who’ as on telly. Spoilsport.

The War Machines have names, not numbers, and the one captured by the Doctor is called Valk. It has no weapons, so the Doctor installs an automatic rifle. Polly and Ben force their way aboard the TARDIS because they feel he’s trying to get rid of them – and not because they’re returning his key.

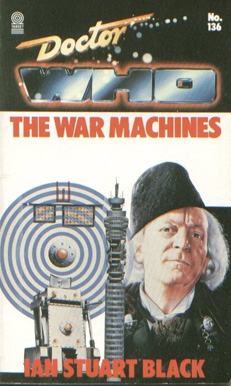

Cover: You really wouldn’t want much more from this cover – a lovely shot of the Doctor, a War Machine and the Post Office Tower, with a close-up of WOTAN’s control panel in the background, broadcasting concentric circles of radio waves. Alister Pearson had help from Graeme Way with the concentric circles.

Final Analysis: Another author delivers his final novel and as with the TV story it’s based on, it’s Ian Stuart Black’s best one. There’s some lovely foreshadowing in Chapter 1 of both the Doctor and Dodo realising this will mark the end of their travels together. That chapter also boasts an introduction to the idea of time travel, and indeed what time itself actually is:

Of course he knew that in one sense Time was a fiction – an attempt by man to measure duration with reference to the sun and stars. But he also knew that although such measurements were based on an impressive formula, all man’s concepts were fraught with error. Time was not as it was supposed to be, for here they were, he and his single crew-member, Dodo, travelling fortuitously across space, splitting Time into fragments – or more exactly, ignoring the passage of time, the rising and setting of the sun, the ebb and flow of tides, the coming and going of the galaxy in which they voyaged.

While Dodo’s departure is only slightly less abrupt than it was in the original, this very swiftly becomes the story of Ben and Polly, who we first met in Doctor Who and the Cybermen (1975). We’ve long forgotten Gerry Davis’s fudging of their origins in those early Target books and they feel as much a part of ‘Swinging Sixties London’ as a story set in the very heart of the ‘white heat of technology’ can possibly allow.