Synopsis: The Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith witness the appearance of a hideous creature on the banks of the Thames. Seeking help at a nearby research station, they discover that a recent meteorite hidden underwater is actually a crashed spaceship. Its inhabitant, a Pescaton, heads for central London on the rampage before it eventually dies. But this is just the first, as soon hundreds of spaceships disguised as meteorites enter the atmosphere of Earth. The Pescaton invasion has begun!

Chapter Titles

- 1. The Darkest Night

- 2. Into the Depths

- 3. Panic!

- 4. A Premonition

- 5. While the City Sleeps

- 6. The Terror Begins

- 7. Pesca

- 8. Creatures of the Night

- 9. ‘Find Zor!’

- 10. The Deadly Encounter

Background: Victor Pemberton adapts his scripts for a story released on LP in 1976. Although the range continues under Virgin Books and is later resurrected by BBC Books, this is the last of the original run of Target books. Just to be annoyingly inconsistent, while Slipback was treated as an extra novel outside of the numbered library, The Pescatons is given a number.

Notes: The Doctor has a poor sense of smell but heightened hearing. Sarah Jane has ‘lovely’, ‘large brown eyes’. The travellers land a couple of miles down the coast from Westcliff, Essex, later confirmed to be Shoeburyness. The Doctor guesses that they’re in the mid-1970s and while we’re later told that they’re reached ‘the seventh decade of the twentieth century’ (which is, er, the 1960s), Sarah Jane also notes that they’re about ten years or so from ‘the period in time she left behind’ – which would suggest the mid-1980s or an unseen adventure.

The first clue of the Pescaton’s approach is a strong smell of fish, then a hissing sound like ‘a jungle cat stalking its prey’.

… eyes glaring like giant emeralds. It was a huge, towering creature, over twelve feet tall, half-human, half fish, with shining silvery scales covering its sticky body, and hands like talons with sharp nails, and webbed feet which were veined in red, heavy and clumsy. Its face was weird, almost gothic; it was like a gremlin, a manifestation of the Devil itself.

A sticky green stuff blocks the route to the TARDIS so the travellers visit the Essex Coastal Protection Unit (ECPU) where they meet 28-year-old head of research Mike Ridgewell and his colleague and longtime girlfriend Helen Briggs. While Mike accepts the Doctor’s claims about an alien creature. Helen doesn’t trust him and is confused by his relationship with Sarah, wondering if she’s his daughter. Mike does the ‘Doctor who?’ joke (first time we’ve had that in a while) and the Doctor replies ‘if you insist’ and introduces Sarah Jane as his ‘assistant’. Mike is a little sharp with Sarah Jane and snaps at her (mild swear-word warning) ‘don’t talk crap!’

The Doctor is ‘not a good swimmer at the best of times’ but he finds the experience of diving to the depths of the estuary ‘awesome’ and reminiscent of walking in space. The Pescaton spaceship is made of a metal he doesn’t recognise. As he leaps from his recovery bed in the First Aid unit of the ECPU, we discover that the Doctor wears ‘long-leg underpants’! When Sarah Jane asks him how old he is, he replies ‘Trade secret’. The Doctor met Professor Bud Emmerson in a ‘previous generation’. Emmerson is in his mid-sixties, with almost white hair, cropped short, and he’s ‘just as fat as he always had been’, which makes his ‘tall, massive body’ look out of proportion with his ‘really quite small’ head. He was a comedy actor in the 1950s but fell into astronomy. He gained widespread recognition for his discovery of a cluster of planets and invested funding from global astronomical organisations and donations from fans to build the North London Observatory on Highgate Hill. The Doctor helped him identify Pesca and the Professor has been studying the planet ever since. Pesca has hardly any ‘ozone protection’ (a major environmental concern at the time of publication).

Mike and a young member of the team called Pete Conway find a beach hut covered in the green substance which has hardened into a shroud shape. Believing a teenage boy is trapped inside, they use a drill to crack open the cocoon, only to discover that Pescatons can mimic human voices – and from the cocoon emerge small, shrieking Pescaton hatchlings, each about eight inches long and instinctively vicious. Seeing a police presence on the banks of the Thames, Sarah gets through a cordon by flashing a press pass (that’s ten years out of date), then the Doctor claims to be from the Department of the Environment. The Doctor recognises a large cone containing thousands of Pescaton eggs, having seen something similar on a past visit to Pesca. The Doctor carries a mini-telescope, a dynameter for ‘tracing sonic direction’ and a flute (replacing the piccolo from the album).

We first encounter Zor in a flashback to the Doctor’s previous visit to Pesca:

A massive creature, with slanting, luminous green eyes bulging out of an oval head covered with shining, metallic scales. Its teeth were sharp and pointed, like needles, and the gills behind its head pulsated as it breathed. And the body! The fins of a killer shark, hands with sharp claws, and the legs of a human stretching down to veined webbed feet. The creature’s tail, which was long and tough, like that of a crocodile, stretched out behind its body but never seemed to move.

…. through those eyes the Doctor could see right inside the creature’s brain, a hideous mass of living energy, a great beehive shape, crawling with minuscule ‘thought worms’.

The creature mimics the Doctor’s speech patterns (so, unlike on the record, it doesn’t have a gravelly North American accent that should be selling us aftershave or narrating movie trailers). Back on Earth, Zor is tracked down to an underground tunnel near Aldwych Station and is destroyed by bright arc lights (on the record, it’s found in a sewer and defeated by high-frequency sound).

At the end, Professor Emmerson watches ‘a small object rising up into space through his telescope’ as the TARDIS departs [in the manner it left in Fury from the Deep on TV].

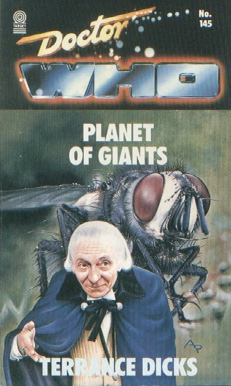

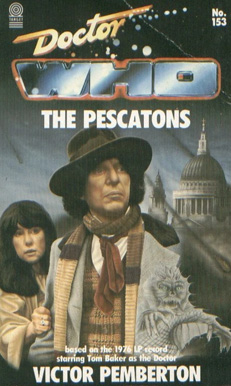

Cover: Pete Wallbank uses a photo reference of the Doctor and Sarah from The Seeds of Doom for a composition that includes the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral and a strange scaly creature that appears to be emerging from the Doctor’s coat.

Final Analysis: Slipback – a radio serial produced by the BBC and broadcast on Radio 4 – was novelised as part of the Target range but not part of the numbered library, putting it alongside the Missing Episodes and Companions of Doctor Who as an interesting side-step that’s not part of the official canon. As the programme itself ceased production in 1989 – and thanks to Nigel Robinson’s determination to fill in all those 1960s gaps – the number of TV stories available for novelisation had reached single figures by this point. Two of those stories were about to be ticked off and the rest would eventually join the Target range 25 years later. While Virgin Books editor Peter Darvill-Evans had successfully launched the New Adventures, starring the seventh Doctor, his past-Doctor range of Missing Adventures wouldn’t hit bookshelves until 1994. Aside from a stage play by Terrance Dicks, there was only one other full story that could be novelised.

Argo Records, a subsidiary of British Decca, released Doctor Who and the Pescatons on LP and cassette in 1976, hitting record stores between the TV broadcasts of Seasons 13 and 14. Tom Baker and Elisabeth Sladen recreated the Doctor and Sarah and it all felt rather like an official mini-episode (the duration for the entire story was just 46 minutes, so akin to a modern single-episode story). And while I listened to the cassette many times, this was the first time I’d read the novel.

Returning to Target after his poll-winning adaptation of Fury from the Deep, Victor Pemberton fleshes out what was quite a thinly sketched story into a full novel. In many ways, it’s a little old-fashioned compared to the later Target volumes. There are some over-familiar SF tropes here: The green, parasitical substance that carpets the south-east of England is straight out of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, while we can look to John Wyndham for sinister meteor showers and a London devastated by monstrous alien beings. Also, possibly a result of adapting the largely narrated album, so much of the novel summarises events, rather than dramatising them – for instance, the Doctor’s previous trip to the planet Pesca and the very accurate and detailed locations around central London (which would make for an unusual walking tour). His approximation of Sarah Jane misses the mark somewhat, casting her mainly as a feed for the Doctor, although she does get to use her journalistic credentials to bluff her way through a police cordon. His depiction of the fourth Doctor is surprisingly accurate though, with a combination of abruptness and other-worldly strangeness.

Where Pemberton succeeds is in creating wholly new characters to populate his world. Mike and Helen take on some of the responsibilities of Professor Emmerson from the record and they have their own dangerous journey of discovery. Then there are the various victims of the Pescatons, who are given distinct personalities and motivations: An obstinate civil servant who ignores the Doctor and comes to a nasty end; the Scottish father and son whose barge is torn apart in a tragic vignette lifted from the pages of Peter Benchley’s Jaws; and a brave young boy and his remote control boat, who is part of a twist that elevates the Pescatons from merely being savage beasts into something much more Stephen King – monsters with sadistic intent.

There’s also a trio of homeless people: Old Ben, who has been a familiar figure in the West End for over a decade; and two teenage boys who have been living rough for about a year. Jess is from Newcastle and he ran away from home because of disputes with his father about being ‘allowed to make his own decisions about how he wants to live‘ and Tommy had heard ‘what a great time teenage kids like himself could have if they moved into the big city’. The italics in both cases are mine and it strikes me that Pemberton uses coded language here to hint at a relationship between the boys that would have been impossible to suggest on TV but would become more overt in the New Adventures. Old Ben is immediately uncooperative with the police, but is more forthcoming with the Doctor and Sarah, which is how they learn of the fates of the missing teens. These three people represent the generational shift in the homeless that, along with ‘the ozone layer’, was becoming a notable social concern at the time Pemberton was writing this (the charitable magazine The Big Issue began publication in September 1991 as a means of both funding support for – and raising awareness of – the rising homeless population in the UK).

In the course of researching this, I fell down a bit of a rabbit hole looking into Canadian actor Bill Mitchell, who voiced Zor on the record. I particularly wanted to know how the man who was the promotional voice of Carlsberg beer, Denim aftershave and hundreds of movie trailers came to play a giant alien fish on a licensed Doctor Who record. This was actually Mitchell’s second role in Doctor Who; he had recorded a scene for Frontier in Space playing a newsreader, but his role was cut from the final edit due to the episode overrunning. As a voice-over artist in much demand in the mid-70s, he spent most of his days in London’s Soho at John Wood Studios and between jobs he could often be found at the Coach and Horses public house – which was also a regular haunt of such notable names as writer Jeffrey Bernard, the artist Francis Bacon – and an actor called Tom Baker…